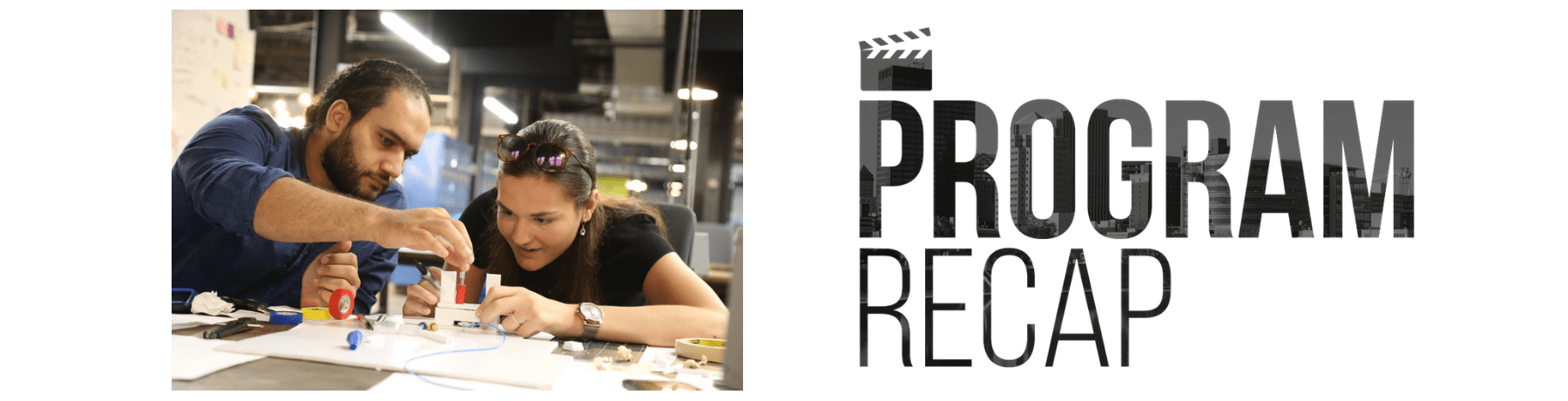

Startup community team develops medical device prototypes in five-day tech sprint

September 4, 2018

In early August, a community team that included engineers, startup ecosystem builders & recent college grads developed two potential solutions to a medical challenge that costs taxpayers millions of dollars per year — and they did it in only five days.

The technology sprint, which was held at the 444 building in downtown Dayton, was the result of collaborative efforts between Ascend Innovations, Downtown Dayton Partnership, Wright State Research Institute’s Dayton Tech Guide team and the Wright Brothers Institute.

“It was a way to really connect the downtown entrepreneurial and innovation community with some of our bigger institutions and their challenges,” Downtown Dayton Partnership Economic Development Project Manager AJ Ferguson said. “We unpack the problem Monday, and as the week goes, we get into a repetitive process — say ideas, blow them up, break them, try again.”

[masterslider alias=”ms-1″]

In the short-term, a sprint is fun and energizing, offering participants “a really raw form of innovation & creativity not readily available in everyday jobs,” Ferguson said.

Long-term, the hope is that ideas that emerge from a sprint become new companies and intellectual property that drive the local economy, he added.

The August sprint was focused on an issue with a Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter — a PICC line. These lines travel through a patient’s vein to reach the heart to enable the rapid, simultaneous release of multiple medications, including powerful antibiotics that cannot be injected through the skin.

One patient that often needs a PICC line is the opioid user, who has higher risk of developing infections due to the environmental conditions of illicit drug use. But an opioid user with a PICC line inserted cannot currently be released to receive antibiotics in an outpatient setting for concern that the line presents an easy access point a patient could use to self-inject opioids, which could lead to an overdose.

Keeping these patients under supervised watch in the hospital limits available beds and costs about $70,000 per five-day stay, according to information consolidated by Ascend Innovations.

Additionally, overdose via PICC lines or IVs can also occur in the hospital when friends or family bring drugs in to a patient. According to one study, 44 percent of illicit drug users admitted to use in a hospital setting.

The issue was brought to Ascend’s attention by Premier Health Director of Operations Ryan Muhlenkamp, who has 13 years of experience in healthcare. Ascend receives projects submissions from the Premier Health, Kettering Health and Dayton Children’s hospital networks.

These patients “need intensive antibiotic treatments, but we can’t complete the therapy outside the hospital because we’re afraid they’d inject via the PICC line,” Muhlenkamp said. “What is a product that would allow us to discharge the patient so they’re safer, and we can open up hospital beds and reduce costs to the taxpayer?”

On day one, the team learned about the issue, interviewing an infectious disease doctor, a risk manager for a large hospital network and medical device experts familiar with the commercialization process. They were challenged to find solutions that could be used across the board to assist potential adoption rates and avoid any HIPPA issues that could occur by distinguishing opiate users from other patients with PICC lines, such as chemo patients.

By the end of the week, the team had 3D-printed and built prototypes of two devices — a digital locking clamp & a plastic locking enclosure, both designed to restrict unintended access to the line.

“Things done for the common good are really easy to inspire passion and focus,” Wright Brothers Institute Rapid Innovation Manager Joe Althaus said. “We had a really strong team, we got mixed perspectives, and the environment was light and airy — it allowed folks to be mobile, dynamic.”

Althaus runs similar tech sprints for Air Force research labs.

“Sprints are the way of the future as far as innovation and tech development,” he said. “They can be applied to software, hardware, even business practices.”

Kaitlyn Roberts, recent University of Dayton grad with an economics and finance background, wasn’t sure what she would be able to contribute to a team filled with engineers — ultimately an idea she had became one of the two final products.

“A lot of my skills revolve around finding problems with things,” she said. “This process gives me space to openly criticize and say, ‘this can be better, let’s push this farther’.”

The short timeline of the sprint also prevents individuals on the team from getting too emotionally attached to an idea they propose, Roberts added.

The different viewpoints were cited as a strength by all of the sprint team members.

“As an engineer, you tend to lock in on how the mechanism will work, how the design will work,” Maria Lupp, Ascend design engineer, said. “It was cool to have others with different opinions come in and help you get out of your own brain and think outside the box.”

Moe Hamdan, biomedical product development engineer and Wright State graduate, had just started a new job with New Jersey-based startup MediSolutions, but he came back to Dayton to participate in the week-long sprint.

The brainstorming process helps foster communication and personal development for participants, he said. Sprints are “cost-efficient and highly effective” across startup ecosystems or even within corporations, he added.

“Being able to foster an environment where you’re sharing ideas and discussing problems is highly valuable,” Hamdan said. The best solution “could come from a simple idea.”

The sprint team also included Kory Gunnerson, Engineering Director at Ascend; Mike Pratt, additive manufacturing research engineer, University of Dayton Research Institute; and Adam Paxton, engineering student heading into his sophomore year at University of Dayton.

In the coming months, Ascend will lead efforts to refine the designs, apply for patents, and partner with local health systems and funders to push a final product to market.